My grandfather was in the Navy during the entirety of World War II. Years ago, he documented his experience from before the war to after its conclusion. I have taken his journals, removed personal identifying information, and am publishing them here. Names have been shorted to initials. The name of my grandmother was changed to “My Love.” What is a story without some romance in it? I hope you enjoy and find them as insightful as I have.

If you missed the first part of this series, you can find it here.

WORLD WAR II: A STORY [PART 1]

WE MEET THE ENEMY

The day after we arrived at Pearl Harbor we were told to remove all wood furniture, radios and certain other items from the ship. Wooden furniture would splinter and burn if it was in an explosion. Radios could possibly tell the enemy our location at sea. All day long a Marine air group moved on board. The next morning we left port. As soon as we cleared the harbor our captain told us we were going to Wake Island, a U.S. possession in the Western Pacific. There was a Marine garrison stationed on Wake, also about 300 construction workers who had been building an airstrip. Our mission was to reinforce the Marines and remove the civilians form the island.

Our task force crossed the International Date Line going West on December 21-22, 1941. Normally anyone crossing the date line for the first time is initiated into the "Silent Mysteries of the Far East." We had no initiations due to the enemy's presence but we were all given "Golden Dragon" certificates to commemorate the occasion.

We arrived in the vicinity of Wake the morning of December 23. Our planes flew over the island and returned, reporting a large Japanese convoy surrounding the island. After considering the odds, our task force commander decided not to attack the Japanese. The next day Wake Island fell to the Japs.

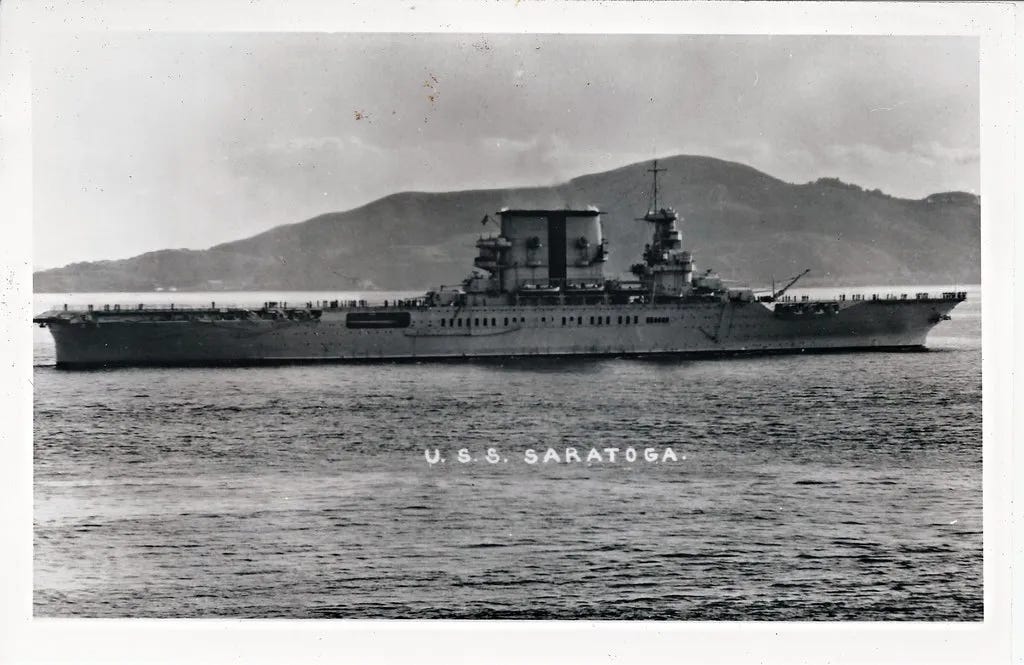

We left Wake and headed for Midway Island, another American outpost. We crossed the International Dateline, going east, on Christmas Day, 10 A.M. Since our crossing set the date back to December 24, the next day was December 25 again. So the sailors on the Saratoga and the other 12 ships in our task force had two Christmases in 1941. Of course, there was no time for celebrating. We sailed on to Midway and launched our marine planes and sent their support group ashore. Most of these young pilots would lose their lives in another Japanese attack in five short months.

We returned to Pearl Harbor, remaining in port only a few days. We headed west again toward Wake looking for Japanese ships. Every morning we were awakened by a bugle blaring "General Quarters" (call to battle stations). It was believed that daybreak and sunset were the best times for submarines to spot ships and launch their torpedoes. We were soon to get our taste of this underwater peril. On the evening of January 11, 1942, as we were returning to Pearl Harbor, we were torpedoed. I was in the "head" preparing to take a shower. The torpedo hit the ship two decks below where I was located. I was blown to the ceiling and must have hit my head as I "saw" a bright flash of light; however, this could have been from the explosion. The lights went out and I started groping my way thru the darkened passageways. I soon reached the lighted area and hurried to my battle station. Later, when I went back to the "head" I realized how lucky I had been. The tile had been blown off the deck and lavatories and other items were laying on the deck. I was unscratched but several men had been killed on the deck immediately below me.

My battle station at that time was an ammunition conveyor which moved projectiles and powder up from the magazines and on to the guns above. We stayed on our battle stations for over an hour while the destroyers in our task force dropped many depth charges, trying to get the sub that torpedoed us. The sub got away and a few days later the Japanese radio bragged that one of its subs had torpedoed a "Lexington type" American Carrier, but did not know whether it sank.

We went back to Pearl Harbor where the dead were removed for burial and a patch was welded over the huge hole in the side of the "Sara." The patch was a temporary "fix" and a few days later we left for the Bremerton, Washington shipyard for permanent repairs. The second day out from Pearl Harbor the patch ripped off and took about 100 feet of the outer "blister" hull with it. Of course our problem was supposed to be top secret but when we sailed into Puget Sound near Seattle, there were thousands of sightseers lining the shores to see the crippled "Sara" come into port.

We remained in the Navy Yard until late April, 1941. While there we were equipped with radar, a new invention. One day while in the yard we were visited by Frank Knox, the Secretary of Navy. All hands were lined up on the flight deck for inspection by Mr. Knox, when a marine orderly ran up and gave a message to the inspection party. We were dismissed from inspection and soon found out that the USS Lexington had been destroyed in the Battle of the Coral Sea.

We were all shocked at the news. We had felt that the Lexington and Saratoga were indestructible. The Lexington caught fire when hit by torpedoes and bombs. The many layers of paint burned so hot that fire on one side of a bulkhead would ignite the other side. Since the fire could not be contained the ship was abandoned and was sent to the bottom by torpedoes from our own destroyers.

With the loss of the Lexington it was determined that all interior paint must be stripped from the interior of the "Sara." For the remainder of the time we were in the "yard" is was pure hell. Chipping hammers operated continuously by both the ship's crew and by yard personnel. In order to sleep, one had to either go ashore or plug one's ears.

BATTLE OF MIDWAY

We left Bremerton and sailed down the coast to San Diego with civilian technicians testing and adjusting our new radars. We were in port at San Diego for only one day. It had been reported that a large Japanese carrier task force was heading east towards Hawaii and Midway. We headed west as fast as we could sail, about 34 knots an hour, to the area where the Battle of Midway was being fought. Actually, the battle was already over when we arrived. One American Aircraft Carrier, the USS Yorktown, and several Japanese ships had been sunk. Many of the survivors from the Yorktown who had been picked up by the escorting destroyers were transferred to the Saratoga for transportation back to Pearl Harbor. Nearly all of the planes based at Midway, including the ones we left there in December, had been destroyed. As soon as we got back to Pearl Harbor, we loaded an Army air group of P-40 fighter planes on board and returned to Midway. None of these pilots had ever flown from a carrier before, but they never lost a plane!

We returned to Pearl Harbor and spent the next two months making short scouting missions to the west of Hawaii. The in late June 1941, we started loading all the ammunition and supplies we could get on board. We left port under secret orders with a large task force of cruisers, destroyers, and supply ships. After a few days at sea, we were told we were to join other ships for an assault on Japanese held islands in the South Pacific.

Normally when a ship crosses the equator, the Shellbacks (those who have crossed before) initiate the Pollywogs (those who haven't). Our task force crossed the equator on July 12, 1942. We had some initiations but there were more Pollywogs than Shellbacks. So the activity was somewhat reduced. Some of the unlucky Pollywogs got their heads shaved and painted purple. Others got beat with canvas straps. And some were half drowned with the fire hoses. Of course, our lookouts maintained their "watches" and our scouting planes remained in the air. I, like most, did not have much of an initiation. We were all given certificates from "King Neptune" making us Shellbacks.

GUADALCANAL

On July 24, 1942, we were about 300 miles from the northern tip of New Zealand. We started seeing other ships on the horizon. Soon there were ships everywhere — 82 of them in all. We had met up with the rest of our strike force. There were two other aircraft carriers in the fleet, the Wasp and the Enterprise. One new high speed battleship — the North Carolina — and dozens each of destroyers, cruisers, and transports carrying the Marine Corps invasion force. We also had several ships of the Australian Navy in the force.

We were told we were going to attack the Solomon Islands which included Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and Bougainville. We headed on a zigzag course back to the north and west. It became known that August 7 was to be the day of attack. As that day approached we had very intense battle drills, I had been placed in charge of a powder magazine in the bottom of the ship. We practiced continually to see how fast we could get the ammo to the guns topside. As "D-Day" approached, I was filled with apprehension — in other words, I was scared. So was everyone else. Before I turned into my "sack" the night before the invasion, I went topside just to look at the stars and to think — and yes, I prayed. I didn't get much sleep that night. About 5:00 A.M. "General Quarters" was sounded and we all rushed to our battle stations. Shortly thereafter, "Flight Quarters" was sounded and we could hear the roar of our planes' engines over the intercom as they departed.

Our first offensive action in the Pacific had started. All day long our planes came and went. They would refuel, reload with bombs and machine gun ammo and take off. We were told by announcements over the intercom how the invasion was progressing. Our marines landed with very little resistance. The planes of the Saratoga concentrated on Guadalcanal, shooting down 11 enemy dive bombers and two twin-engine bombers. Japan lost 42 planes and 42 of their best pilots in the action on August 7 and 8. We lost five fighter planes and pilots from the Saratoga. The planes from other carriers attacked other islands in the Solomon group. Things went so well that we were allowed to leave our battle stations about 3:00 P.M. I went topside and I could see a beautiful tropical island off the port side of the ship. That was Guadalcanal and it didn't stay beautiful long. In the weeks that followed, the beautiful palm trees on the shore were reduced to stumps by the fighting between the marines and the Japs who returned from the jungle to fight.

My visit topside that afternoon got me into a lot of work. Our bombers had just returned from hitting some of the enemy's position on Guadalcanal and all had to be re-loaded with bombs. The officer in charge of the loading detail saw me and I spent the next hour pulling bomb-carts to re-arm our bombers.

Early in the morning on August 9, 1942, a Japanese surface force engaged some of our cruisers and destroyers who were covering troop landings in Tulagi harbor. There was so much confusion and it was reported that some of our ships were shooting at each other. Our cruisers USS Quincy, USS Vincennes, and USS Astoria were sunk. Many other American and Australian ships were damaged. There was no report of any Japanese ships being lost!

We stayed in the vicinity of the Solomons, our planes flying sorties each day to attack enemy shipping or to cover our marines' ground operations. On August 23, our planes spotted a large Japanese fleet moving down from the north. We were told that it was going to be a tough battle. The Japs had three aircraft carriers in their task force. We had four carriers in the area. On August 24, we went to our battle stations before daybreak and our planes flew off to strafe, bomb, and torpedo the Japanese ships. The Battle of Eastern Solomons raged on for two days.

It was tough being in a powder magazine in the bottom of the ship with air battles going on "top-side." We had to remain there all day long. We were locked in with all hatches between us and "top-side" "dogged down." On the second, one of my men broke under the strain. He started "un-dogging" the hatch above us and said he was going to "get the hell out of there." I warned him not to go that he might be shot for deserting his battle station. He went anyway and we "dogged" the hatch behind him. He was arrested "top-side" and was later court-martialed and give an "undesirable" discharge. He would have been treated more harshly, but he was a survivor from the USS Yorktown which was sunk at Midway and now was considered mentally unfit for further service.

During the battle, our carrier Enterprise was hit several times and had to be towed from the area. But the Japs suffered the greatest losses. The planes from the Saratoga sunk one carrier and one destroyer. One battleship and one cruiser was badly damaged. I do not know how many ships were sunk or damaged by the other air groups.

During these battles several of our planes were lost and their crews were killed. Others that were shot down were more lucky and were picked from the water by our destroyers. Some made it back to the ship only to die from battle injuries. After the battles had stopped these were placed in canvas "caskets" and buried at sea. Our Chaplain conducted a brief service and as taps was played by our bugler, one by one the flag draped stretchers bearing our fallen shipmates were tipped and they slid off and sank into the sea.

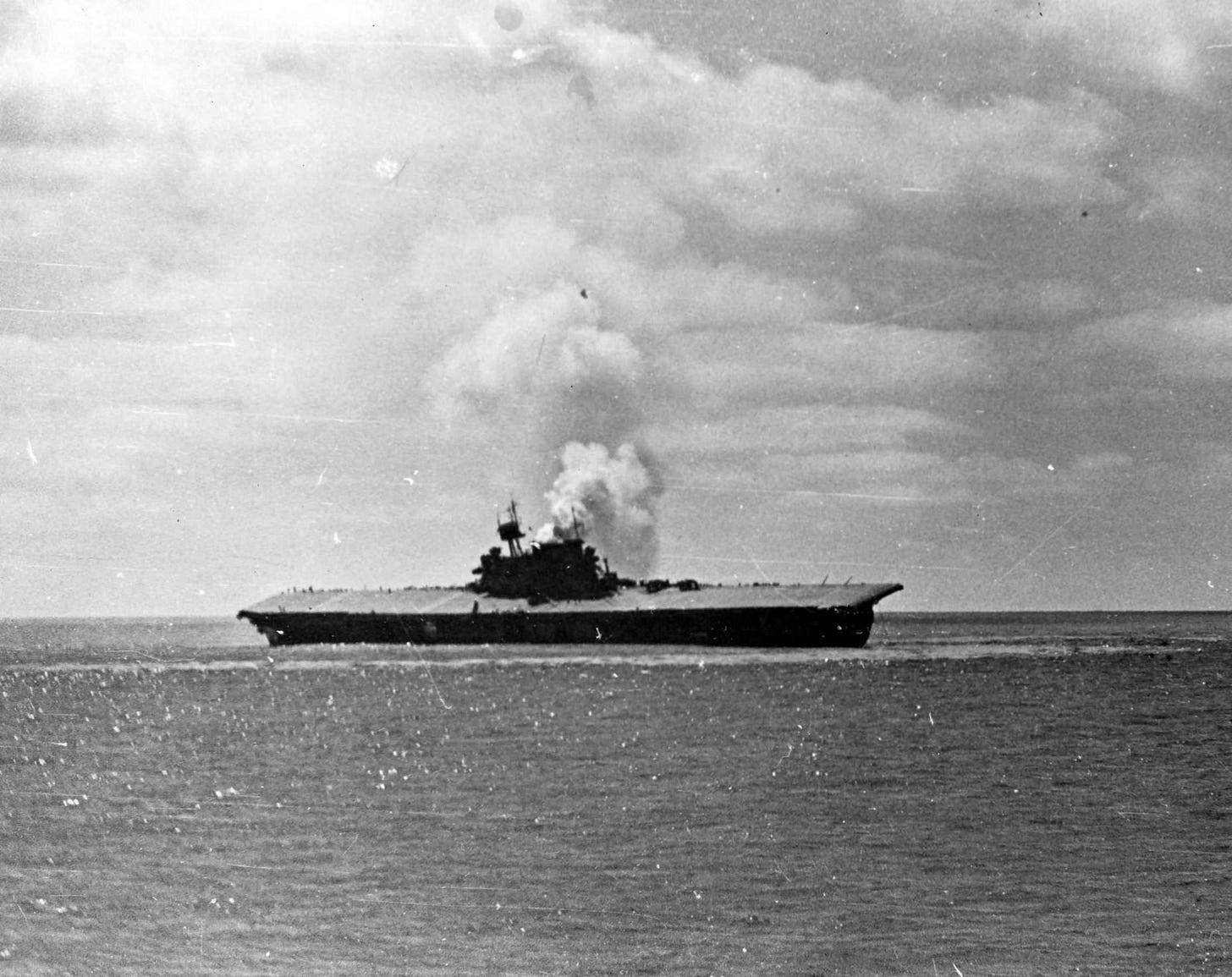

OUT OF ACTION

On the morning of August 31, 1942, we were sailing peacefully along when a tremendous explosion shook the ship. The bugler immediately called "Torpedo Defense" over the intercom and we all rushed to our battle stations. We had been torpedoed again by a Jap sub. Our destroyers immediately started dropping depth charges on the sub and it was probably destroyed, but the damage was already done. The Saratoga's main control system had been hit and we had no power. A tow line was fastened to the "Sara" from the cruiser Minneapolis and we were towed form the area. The next day temporary repairs were made and we were able to move under our own power. We sailed in a south-easterly direction and arrived at Tongatapu in the Tonga Islands on September 6, 1942. We were very low on rations. We had lost some storerooms from the torpedo and were subsisting on red beans and rice. When we entered port one of our supply ships the USS Arctic was there. Food supplies were brought aboard immediately and that night we had "Christmas" in September — a big turkey dinner.

This was certainly an enjoyable time for those on the Saratoga. It had been two and one half months since we sailed from Pearl Harbor. After spending days at a time on our battle stations, going on limited rations, and being torpedoed, the beautiful surroundings of Tongatapu harbor seemed like heaven to us.

Engineers from the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard were flown to Tongatapu to survey the ship's damage. While waiting, we were able to go ashore on liberty but there was not much to do there. Tonga was one of the most primitive island groups in the Pacific. On September 12, 1942, we joined the USS South Dakota, a new battleship, which was also damaged, and started for Pearl Harbor.

When we sailed into Pearl Harbor on September 21, 1942, I experienced one of the most touching events of my life. The crews of every ship in the harbor were on deck in assembly formation and saluted us as we passed. Bands were playing and as we passed, the ships horns were sounded. Heroes or not, for the moment at least, we were made to feel like heroes.

We were in the Navy Yard at Pearl Harbor for just three weeks. Our boiler-rooms that were damaged by the torpedo were not rebuilt. It was determined that the Saratoga could operate satisfactorily without them. Steel plates were welded over the gaping hole in the ship's hull. Then concrete was used to reinforce it. Then out we went — back to the combat area. While we had been laid-up, things had not gone well for our Navy. Two of our aircraft carriers had been sunk by the Japs — the Wasp and the Hornet. Our only new battleship in the area, the North Carolina, had been damaged and withdrawn from the Solomon Island area. Of course, the Japs didn't know it, but we were on our knees. Everyone of our "Capitol" ships, eq. battleships and carriers, in the Pacific were out of action, either sunk or damaged.

We made our way to the Fiji Islands. We remained in the harbor at Lautoka, Fiji for almost three weeks. Lautoka was about 800 miles from Guadalcanal and we were able to monitor the area for enemy ships from that vantage point. I was able to go ashore two times while we were in Lautoka. It was very similar to the port of Tongatapu — just a native town of a few hundred Polynesian people and a sprinkling of white coconut plantation owners.

On December 2, 1942, we sailed for Nouméa, New Caledonia which was about 500 miles south of Guadalcanal. It was the location of the South Pacific Naval Command under Admiral Wm. F. Halsey. We arrived at Nouméa in three days. Nouméa was a city of a few thousand people — about half of them French. The French people were descendants of a French prison colony which had been there years before. They were very hard to communicate with as very few professed to speak English.

Surprisingly Nouméa was not blacked out at night like Honolulu. Lights were on at night as though the enemy were thousands of miles away, not just a few hundred. In fact, I went ashore on New Year's Eve, 1943. The natives had a big street dance and celebration in the town square that night.

We stayed in Nouméa for 12 days, then we headed back to the Solomons. Heavy naval engagements had taken place there during the previous two months. Our losses had been heavy — two carriers, two cruisers, seven destroyers and damage to seven other vessels, but all was quiet now. The Japs had suffered tremendous losses and had retreated to the north and west. We returned to Nouméa on December 27, and I was not to see the Solomon Islands again. On January 5, 1943, I was transferred to the shore base of Commander, South Pacific at Nouméa for transportation back to the United States to go on a new aircraft carrier. I was ecstatic — maybe I would get to go home on leave. I had not been home for two years.

I had been writing to My Love ever since I joined the Navy. Although we had never dated in high school, through our correspondence, My Love had become very dear to me. Now, I thought I might get to see her again.

I was at the Naval Base in Nouméa only four days. A tropical storm was approaching Nouméa and all of the ships were ordered out of the harbor. Those awaiting transportation to the U.S. were rushed aboard the transport USS President Grant, a converted luxury liner. The sea was very rough because of the approaching storm. We could not use the gangway and had to climb a cargo net to get on board.

When I got on board the President Grant, I looked out across the harbor and saw the Saratoga leaving the harbor. I never saw her again, but the planes from her flight deck continued to hit the Japs, battle after battle, all the way to the Japanese mainland. She was torpedoed and bombed many times. At the war's end, she was no longer considered an asset to the Navy and was sent to her grave in the lagoon of Bikini Atoll during an atomic bomb test in July, 1946.

TO BE CONTINUED…

Thank you, so much for sharing this with us, Elizabeth. It is like one can visualize everything, and it also brings memories back from when my Dad was in the Navy, the stories he told. Thank you.

Compelling and fast read. You feel like you are there with him. Some bittersweet moments.